We should focus instruction on rigorous, content-led, subject-specific tasks

that ensure students think hard about subject content.

It is my belief that we need to change the way we think about planning and instruction.

In his book First Things First, Stephen Covey suggests changing the way we think about time: from the clock to the compass. Clock thinking is working out how to get more and more things done. Compass thinking is working out which things to focus on in the first place.

In teaching, it strikes me that we are stuck in clock thinking. We think about planning and evaluating individual, ideally ‘outstanding’ lessons. This pursuit of the ‘outstanding lesson’ is a chimera, spawning innumerable INSETs and entire book series.

Is the road to hell paved with outstanding intentions?

As Professor Coe has pointed out, this risks focusing our attention on poor proxies for learning:

But there’s no point criticising without suggesting an alternative. Last weekend I promised a constructive alternative to lesson planning for fun, generic activities that risk distracting students from thinking about subject content.

The alternative as I see it is to think about activities last of all, and design the entire core content of the unit and its assessment first. Rather than focusing on individual lessons, we need to refocus on entire units, and the sequencing across and between them. This is a phenomenal amount of work: Katie Ashford and I spent around 500 hours between us planning and resourcing this one unit on Oliver Twist. The topic of my next post will be how we might evaluate such units.

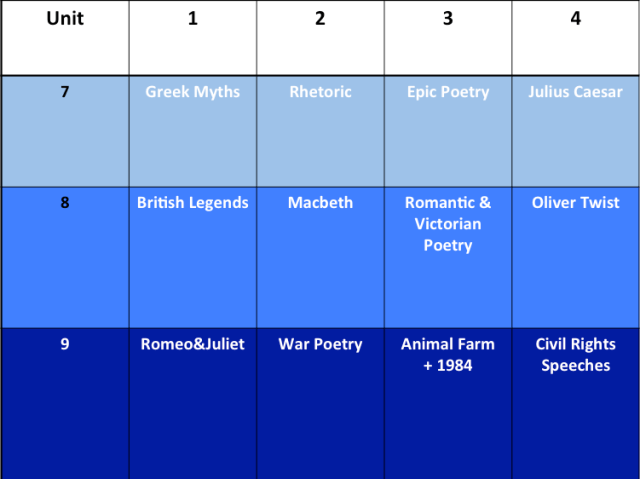

Example curriculum overview: co-planned with Katie Ashford

Example knowledge grid: Katie Ashford’s Oliver Twist

Example lesson questions: Katie Ashford’s Oliver Twist

Example unit sequence: Katie Ashford’s Oliver Twist

Then, and only then, after specifying and sequencing the unit’s knowledge, can we refocus on rigorous, subject-specific tasks that ensure students will be thinking hard about subject content. It only makes sense to think about activities once you have considered what knowledge pupils need, and in which order.

What exactly do we mean by rigour? The litmus test for each task is Professor Coe’s simple theory of learning: will it help students think hard about subject content?

To my mind, rigour in teaching is all about the effective transmission and retention of knowledge in pupils’ long-term memory: if tasks don’t focus students on subject knowledge, then they’re not helping students learn.

For now, I just want to focus on the rigorous tasks that I’ve found most effective for instruction in one subject: my subject, English.

For me, task selection in English depends heavily on which genre – whether poem, play, novel, nonfiction or grammar – and which content – context, author, plot, characters, themes, language, structure, form or concept – I am teaching.

Nevertheless, here are some (non-exhaustive) tasks that I have found most useful for English, roughly in order of increasing complexity:

- Record the lesson, essay or exam question and underline the key words.

- Record a checklist of criteria and highlight the key words.

- Reading aloud in (irregular) turns, whole-class line-by-line with a ruler.

- Whole-class pose-probe-bounce stretch-questioning, no-opt-out.

- Read question; then discuss in pairs; then share as a class.

- Underline key quotations, highlight key words; then justify choices in pairs.

- Write short (even one-word) answers to 20 ‘do now’ written questions.

- Sequence these in order (episodes in the plot, characters in importance)

- List and collate examples (of characters, themes, concepts) or ideas.

- Listen to explanation of a concept with an example/non-example sequence of questions.

- Decide whether these (context, plot and character) statements are true or false.

- Mindmap and collate examples or ideas for characters, themes or language.

- Answer 10 or so plot comprehension questions (& ‘why?’ extensions) in full sentences.

- Complete a spelling quiz or test & mark each other’s.

- Match vocabulary & definitions/synonyms/antonyms, or vice-versa.

- Match dates and events in a contextual timeline.

- Categorise examples (of characters, concepts etc) into columns.

- Discuss multiple-choice hinge-questions with distractors in pairs.

- Discuss hinge-question answers, misconceptions and justifications as a class.

- Complete multiple-choice quiz on core content (between 10 and 50 questions).

- Free recall test on 10 context or character questions.

- Create sentences with examples of concepts.

- Annotate model paragraph for content/techniques/criteria.

- Give peer-assessment feedback with clear criteria-based questions.

- Compare model sentences for the differences in quality of criteria.

- Write a sentence with a rigorous conjunction (although, at first glance, overall, ultimately, etc).

- Create a free sentence ready to share in pairs and with the class.

- Write answers to ‘exit ticket’ questions on concepts or content.

- Plan essay ideas in a graphic organiser (grid/matrix/flow diagram).

- Summarise the text/plot/characters’ journey in a paragraph.

- Find similarities and differences between characters with a focus (first/last impressions).

- Summarise the text/plot/characters’ journey in a paragraph.

- Compare two introductions and evaluate which works better and why.

- Compare two conclusions and evaluate which works better and why.

- Write an analytical paragraph on a character, theme or concept.

- Write a comparative paragraph on characters, themes, concepts, chapters or poems.

- Read each others’ essays and write extension questions.

- Redraft the story/poem/biography/speech/essay with corrections and improvements.

- Create a (gothic/ghost/etc) short story (e.g. 200 words) or poem (limerick/haiku etc).

- Write an informative biography.

- Write a persuasive speech.

- Convert the speech to notes and memorise it.

- Practise, rehearse then deliver the speech.

- Write an analytical essay (with context).

- Write a comparative essay (with context).

… and there are probably 45 other tasks you could list – and more. The vital distinction is in connecting these tasks to subject content to ensure students are thinking as hard as possible for as long as possible about the right things. Ultimately, it is how to connect these still-generic tasks with specific subject content that matters most.

How are these tasks more rigorous than others? They focus pupils’ attention more on thinking carefully about subject content, and they risk less distraction from it. They prioritise retention rather than variety for its own sake. Tailor the task to the content, rather than vary activities for pupils’ supposed learning preferences. First things first: first content, then (and only then) activities.

Of course, spelling, grammar and vocabulary are a different story. So are creative writing and public speaking. They require unique, tailored tasks, beyond the scope of one blogpost. The point is, activities are best when subject-and-topic-specific, not generic.

From the clock to the compass: the thinking shift is from planning lessons for engaging, generic activities to selecting and sequencing rigorous, content-led tasks across units. The key difference is the pursuit of the optimal mode of knowledge transmission, retrieval and retention.

The guilty secret of the “outstanding lesson”: a chimera that never existed at all

***

Over the next few weeks I plan to write about unit evaluations and essay questions in English. Meanwhile, please add to this emporium of English essay titles and questions.

Thank you for this. I have an instinct in my mind that there is a (slightly shorter) list of appropriate tasks in maths, as I know I default to it unthinkingly. Reading this I’m realising the value of listing them and examining them more explicitly to (a) assess their merit and (b) consider further refinements. It would be interesting to see if, like in TLaC, a list of subject/topic specific techniques/tasks that push learning could be defined and improved. As in, the (close to) perfect form of a task on “identifying errors in working” etc etc. even writing that, I’m realising how woolly I’ve been! thanks for the thought-provoking post.

I do think formulaic approaches are really helpful earlier in your career Joe, but too much control leaves children without space to imagine. I’d be really interested to know how you think these lessons fit in with your model – genuinely – if you have the time 🙂 http://debrakidd.wordpress.com/2014/02/21/faith-hope-and-hilarity/

500 hours? Blimey. We need to get lives.

Reblogged this on Primary Blogging.

Reblogged this on The Echo Chamber.

The clock has ticked it’s way through my long career from pre NC knowledge gathering, through -[certainly in my original subject, history] a plethora of skill based activities back to the growing clamour for deeper learning of subject specific tasks. I can accept that learning does require hard and purposeful thinking and that if the cult of individual outstanding lesson exists in a school-it would restrict learning. I’m not sure that it does everywhere. The end product of a period of pedagogy and planning, whether it be an exam grade, lesson study project, research based innovative block of learning etc. demands an anticipated learning gain over time from the teacher and then reflection on how different teaching tactics [like your 45] impact on learning-if a school thinks like this [and many do] your worry about poor proxies, dodgy compasses and individual lesson will chimera off!

There is also room for Debra’s lesson too! The children will have been engaged and learning will happen-both your formula and her wizardry have the same aim of focus and retention to make learning stick. I would never want to return to telling teachers there is a ‘right way to teach’ and nor I guess would you. Nor would I mention 500 hours as SLT when talking about planning-they’d down tools! I do enjoy your blogs-you raise great discussion points and I certainly will be encouraging my colleagues to connect their tasks to subject specific learning and evaluate impact. Thank you for sharing so openly and honestly.

Pingback: Free Thinking: I agree with Katharine | Pragmatic Education

Pingback: The Case for Design in Curriculum | thinkingreadingwritings

What you describe is precisely what Understanding by Design was built to do: teach educators how to design units ‘backward’ from long-term goals and aligned assessments, with a focus on deep understanding.

Pingback: The Clock & The Compass: Rethinking Instruction | Pragmatic Education | Learning Curve

Pingback: A guide to this blog | Pragmatic Education

Pingback: The Signal & The Noise: The Blogosphere in 2014 | Pragmatic Education

Pingback: What Makes Great Teaching? 6 Lessons from Learners by @Powley_R | UKEdChat - Supporting the Education Community

Pingback: Articles | Joe Kirby